From Muse to Maker

Why is it Important to Celebrate the Women Surrealists?

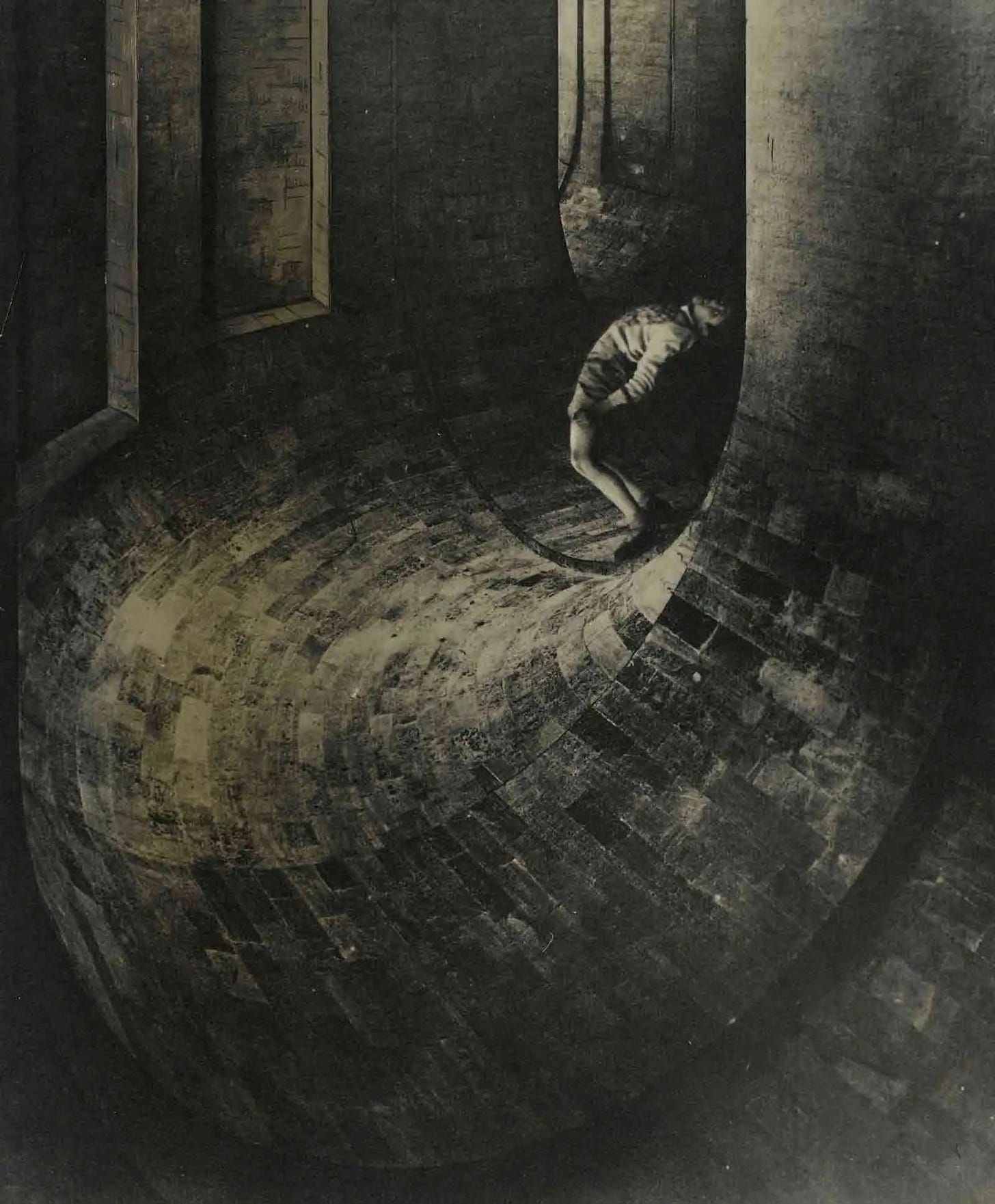

I’d like to guess that you have heard of Salvador Dali, René Magritte and Marcel Duchamp but how many women artists of the surrealist movement of the 1920s and 1930s can you name? This isn’t just about history. In the words of Billie Jean King: ‘you have to see it to be it’ and I strongly believe that to be deprived of female models is to be deprived of possibilities. For instance, while we keep on remembering Dora Maar as Picasso’s muse, we miss out on knowing that a woman was pioneering surrealist photography in parallel to Man Ray, and doing it very differently.

We need to broaden and reinstate the origins of surrealism by putting the women back in as makers, not just muses for great men. Surrealism is about the freedom of the imagination. It’s about rebelling against any form of constraint: against respectability, against the rules of art and against believing in received histories of art.

Art as an old boys’ club

It is always brave when young men refuse the dictates of society in the name of freedom and art, but for women to do this is even riskier. Women have been censured and punished for behaving freely, and the enclave of fine art has been closed to them in many different ways throughout history. Art has been an old boys’ club for centuries: men have created, sold, bought and critiqued art between them, and the most usual place to find a woman in all of this has been on the canvas, often naked. I am exaggerating, of course, but not by much. Women were barred from many aspects of art training up to the late 19th century and it was only occasionally that women artists participated in art movements or exhibited alongside men. Then came surrealism.

At first the movement was confined to words and poetry and, led by André Breton in Paris in the 1920s, surrealism was also a boys-only club. Women were not included in their gatherings, manifestos, magazines or books apart from as secretaries or lovers. In a groundbreaking series of published discussions about sexuality and sexual behaviour, only after several sessions did one of the men think to question why no women were part of the discussion group! And then something changed.

Surrealism in the 1930s: the women arrive!

In the 1930s, surrealism began to spread into visual art. The paintings and sculptures that we now associate with the surrealist movement began to appear and it was at this time that gifted young women artists began to arrive in Paris and associate themselves and their work with surrealism. They were often the partners of the male surrealists and often a lot younger than them. These women, from the UK, Switzerland, America, Czechoslovakia and other places, had taken the principle of freedom preached by surrealism to heart. They were risking a lot to throw over the security of conventional women’s lives. Some, like Dora Maar, paid the heavy price of mental breakdown and Nadja, the epitome of surrealist freedom written about by Breton in one of the best-known surrealist books, ended up confined to a psychiatric asylum.

But women such as Leonora Carrington, Meret Oppenheim, Lee Miller, and Toyen were ahead of their time and, despite being denied all the social changes that have happened for women since, they created lasting artworks and lived life on their own terms. They lived surrealism at a time when women were still not full citizens under the law and were expected to be first and foremost wives and mothers.

Surrealism welcomes women, then forgets them again

Surrealism as an art movement was unusual in welcoming women as artists. This was partly because of the emphasis on freedom and transgression which extended (up to a point) to the attitude to women and women’s roles. So, although the individual attitudes of the male surrealists were often sexist and of their time, nevertheless surrealism as a movement was the first to include a large number of women in its ranks. Over time, however, the old boys’ network took over again. The women surrealists’ work was not exhibited, nor were their names mentioned alongside the male ‘superstars’ of surrealism such as Dali, Magritte and Picasso. It took the women’s movement of the 1970s and the dedicated work of feminist art historians and curators of the 1980s onwards to retrieve, critique and exhibit their work. It is an incomplete project.

Now is the time to honour the women of surrealism

Last year marked the 100th anniversary of the Surrealist Manifesto of 1924 and I am determined to play my small part in making sure that the women of surrealism are remembered. I want to do this to put the historical record straight but I also have a personal connection to the women surrealists because of the direct and enriching inspiration I draw from their work. It was to honour this. and to share that inspiration, that I decided to create my series of experimental imaginary encounters with surrealist art by women for this newsletter, The Fur Cup

Muses and makers

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the women surrealists have become my muses and my novel, Swimming with Tigers, is based on some of their lives. The women of surrealism have enriched my life and I want to ‘pay it backwards’ by featuring and promoting their extraordinary paintings, sculptures and writings. In helping to rescue their work from obscurity, and playfully presenting it in my writing, I hope that the women surrealists will inspire you, as well.