Instead of an imaginary encounter with an artwork, this time I am describing an imaginary encounter with one of the women surrealists herself: Leonora Carrington.

It is 2008 and Leonora is 91 years old. She sits in her kitchen in Mexico City wearing a woolly jumper and smoking Marlboro cigarettes, as so brilliantly described by Joanna Moorhead in her biography The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington.

The conversation is necessarily one-sided because it occurs after Leonora’s death. However, she had the reputation of a very tough interviewee who was reluctant to answer questions and often turned the tables on her interviewers, so it is unlikely that she would have answered my questions even if I had been lucky enough to meet her or foolish enough to make such impertinent enquiries.

Interviewer: “Thank you for agreeing to talk with me today, Ms Carrington. Is it always so cold in your home? I wanted to start by asking you about the house you grew up in, another chilly place, I suspect, namely Crookhey Hall in Lancashire. Your father was a wealthy man I believe and your mother was Irish. I'm particularly interested in your nanny, Mary Cavanaugh, who seems to have been the one to tell you stories of Irish lore and tales of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the ‘wee’ folk. Were her stories, and the influence of your Irish grandmother, more important, perhaps, and the surrealist imagery you encountered first in Herbert Read's book and then by going to live in Paris in 1937?

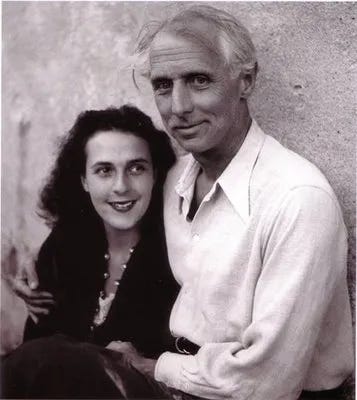

“I'm sorry if you think that was a simplistic question. I'll move on. You've been reluctant in the past to talk at length about your intense relationship with Max Ernst but it is such a romantic story: a young girl rebelling against her privileged background and authoritarian father, leaving England despite all parental opposition, learning from Max who was 26 years your senior and putting up with his jealous wife, an idyllic life in the south of France that was ended by the war. Even the complicated ending of the relationship is screen-worthy: the time you spent in Lisbon when Max had thrown in his lot with Peggy Guggenheim (who fell in love with him but knew that he still loved you) and, once all of you had escaped war-torn Europe, another heartbreaking situation in New York. Why did you finally break from Max and go to Mexico? Joanna Moorhead is sure that you no longer loved him and feared he would overshadow you. Is she right?

“I do apologize. I knew you preferred not to talk about this but I didn't realize how very angry it would make you. Let's just clear up this broken crockery, then continue. Thank you, and I do most sincerely apologize. I'd like to ask about your extraordinary account of the time you were held against your will in a mental asylum (as they were then called) in Santander in 1940 which is called Down Below. It is a harrowing account of being forcibly 'treated' with seizure-inducing drugs and you describe in great detail the psychological and physical unravelling you experienced. It's astonishing that you recovered and went on to paint, have a family and live to very old age. My question is do you regret making that episode of your life public? Also is it, as Conley suggests, a sort of riposte to Breton’s book Nadja and the general idealization of madness, especially madwomen, by the surrealists?

“Fine. I understand you would rather not comment and yes, I will be brief. I have a few more questions and that's all. I want to come on to your time in Mexico in the 1940s up until your decision to leave during the political protests and crackdown of 1968. Did you identify yourself as a Mexican artist, having married Chiki Weisel, a Mexican photographer and friend of the famous Robert Capa, and bringing up two sons? Also, can you speak about the effect of the tragic and premature death of your close friend Remedios Varo, a surrealist artist like you, in 1963?

“No, I can see how insensitive that must have sounded. Apologies, once again. Let me ask a more straightforward question about money. Joanna Moorehead writes that you were so poor when you lived in New York in the 1970s that you ate ice cream because it was a cheap way of consuming calories. Is this true? Why did you actively ignore the important side of being an artist: approaching galleries, cultivating a network of influential people and making sure the public knew about you? Your paintings are sold for millions now, you know, and it's hard to understand why you would have been so poor that you are unable to pay the rent on a bedsit in New York.

“Well, maybe I do have a basically flawed understanding of the artist's life and priorities but there's no need to insult me like that. My final question is about your relative, Joanna Moorhead, whom you seemed perfectly willing to befriend and confide in, unlike me. Getting to know a member of your family after a lifelong estrangement from them must have been very significant for you. Did you regret never returning to England?

“Thank you, Ms Carrington. I will indeed mind my own business in future. Before I leave, can I ask if you have any further comment on the question Whitney Chadwick asked you in the mid-1980s, namely your view of the position of women in the surrealist movement as muses to the male artists? On that occasion you used the word 'bullshit'. Since that time I am sure you have been pleased to see the interest in women surrealists’ work because I know you were connected to the early women's liberation movement in America. Frida Kahlo, for instance, would, I think, be amazed to know that her profile is much greater than her husband Diego Rivera's and there is every reason to expect that in the future many people will know your name and work more readily than Ernst’s. I hesitate to mention this, but I have in fact borrowed episodes of your life to include in a novel I am publishing soon. I am relieved to see you smile, Leonora. Would I be right in saying that creative projects are much more interesting to you than journalists' questions?

I’d love to hear what you think of my imaginary encounters! Click on the button to leave a comment on my story and join in with the Fur Cup conversation.

I really enjoyed this imaginary interview! Interviewers so often lack the patience and finesse to ask questions with the intention of listening to the response. Even in an imaginary interview your pauses and humourous acknowledgement of Carrington's displeasure is admirable. :)

Nicely handled humour riffing on actual Leonora interviews