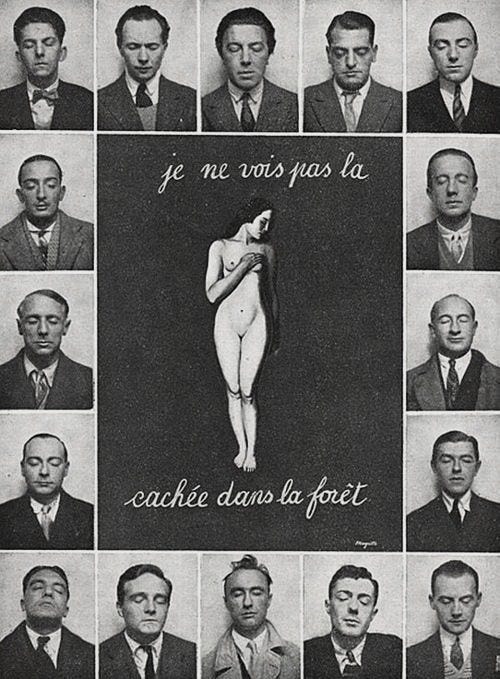

This is an illustration from a surrealist magazine published in 1929. It shows the members of the surrealist group at the time, all with their eyes closed, arranged around a female nude that recalls the depiction of Venus in the fine art tradition. Now, just for once, the goddess Venus gets a chance to speak up and consider what she is doing in this picture.

I am Venus, the goddess of love, and I have visited many pictures and sculptures in the past. I have inhabited the now sadly truncated form of the Venus of Milo, slipped into the ideal woman of Titian’s Venus of Urbino and hovered around the questionable body of Manet’s Olympia. If you’ve no interest in these high-class incarnations, you’ll find me in adverts for perfume on TV or in the gentler forms of pornography. I’m sex, yes, but sex as a remote dreamy physical pleasure melting into myth. That’s my trademark: the myth of beauty. I am it. Beauty itself, which has more or less always appeared as a woman’s body, white and hairless. Useless, really, to mention how narrow that is. I was delighted when they found those tiny figurines of me in Germany where I have massive breasts and a huge, bulbous stomach.

It was Botticelli who started the craze for having me emerge from the sea. That part of the story of my birth, in which I arrive calmly riding on a shell or fetch up naked at the water’s edge, is preferable it seems to the earlier part where Jupiter cuts off his father Saturn’s penis and throws it into the sea, and the blood and foam create me. That was a skewed version of biological conception but it does set the pattern: I have always been between two men, or seen in relation to men.

But how did I get into this picture from 1929, surely too late for the goddess of love to make an appearance? This isn’t a pretty painting designed to be hung in a palace. It's from a surrealist magazine, La Révolution Surréaliste, and the painter I visited was René Magritte. (He’s the second from the bottom, on the right.) I’m not named, but you can see it’s me by the way I stand, holding my arms in a way that displays my naked body while seeming to hide it.

The newest aspect of this appearance of mine is that the men who have summoned me and desire to look upon me are also in the picture. They are depicted in a different medium to me. I am painted, but they are photographed (by Man Ray, who is not included). Mostly, I’ve been openly ogled by men while their wives try to keep a neutral expression. Some women, like Mary Richardson, the suffragette who slashed the Venus of Rokeby in 1914, dared to make a fuss about this tiresome, repetitive idealisation of ‘Woman’ when real women are at the bottom of the heap. Yes, the feminists have been objecting to me for a long time now but I can’t help arriving when men continue to call me up. So far, it’s generally been men but I am willing to answer if women artists call and I wish more would try. I don’t always have to look the same as I did in the past, after all.

In 1929, though, it’s just me and the men who, surprisingly, take their place next to me in the picture and are shown as the dependent, rather desperate, individuals they generally are. At least these men have names and personalities, while I’m still the same as when I was a chunk of rock: a representation of every woman, and none.

You’ll have seen that the men’s eyes are closed. Strange. All the men have liked looking at me before. The words say ‘I do not see’ then it’s my image to replace and represent the word ‘woman’ followed by ‘in the forest’ as though the dreaming men can’t even say my name. Do I scare them? Am I beyond them, above them? I suppose I am their unconscious: I believe the unconscious was very important to them.

The surrealists certainly worshipped me—love was the highest ideal for them and sometimes they approached a real appreciation of the feminine that was different to the usual version of women as an adjunct to men meant only to bolster their ego and provide sexual pleasure, hot dinners and offspring. The surrealist men wanted nothing to do with docile, domestic women and that was new. But still, here I am, being painted the same way, more or less as, in the 15th century: I am as blank, featureless and perfect as a cube of white sugar.

The Romans put me on their coins, but I dislike money and greed. It’s art and human passion I belong with and the latest attempt to lure me into helping to sell razors to women disgusted me. It wasn’t just beneath me, it was wrong. I have a more complicated relationship to real, living women who buy things from shops, and that’s exactly the problem you will all have to work out. I’d like one day to be able to visit as a man (Björk sang it: Venus as a Boy). It’d be complicated, but worthwhile.

In the future, I hope to be with you in many different forms.

Hope that a group of female artists have created a parody of that cover! Thanks for sharing - reveals so much.