I am in an art gallery standing in front of Leonora’s self-portrait when suddenly, by the power of surrealism, I find I am able to step inside the picture. Come with me, then, as I wander around in this strange world.

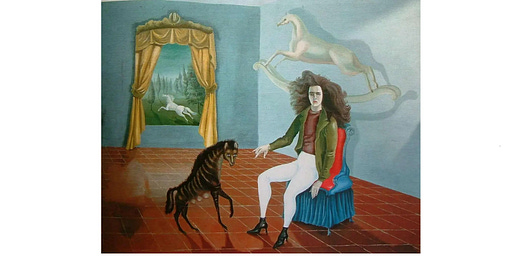

I am stepping cautiously into this magic painting, a self-portrait sometimes referred to as The Inn of the Dawn Horse. It is a bare room in which a young woman sits surrounded by strange animal totems. There is plenty of empty space to walk around on the tiled floor. I am aware of two pairs of eyes upon me: the woman’s and the hyena's. They are both staring hard at me and noting my every move.

The young woman sitting in the chair is the artist, Leonora Carrington. She was brave as a girl and terrifying as an old woman. She had the courage at a young age to leave her upper-class family in Lancashire and go to live in Paris as part of the surrealist group in the 1930s. I have borrowed aspects of her life for my soon-to-be-published novel, Swimming with Tigers, and this makes me nervous of her judgment (even now, years after her death in 2011). But I am also emboldened by all that I know from reading about her, seeking out her pictures and her stories, and also her own novel. She stayed true to herself through war, exile, mental breakdown and poverty, making art because she was driven to do it and never as self-promotion or for purely commercial reasons. She continues to astonish me with her creative gifts, and her bold decisions inspire me. Her bloody-mindedness, too.

So here is Leonora as she saw herself in 1938. Four ‘creatures’ accompany her. First, there is the chair she sits in, which could belong to either boudoir or nursery. I step carefully to the right and bend down to inspect it. She allows this, waiting to see what I will make of it. I touch the red seat and the back of the chair. It is plush and plump. The pleated blue skirt around the legs is smooth velvet. Looking further down, I see that the chair legs are wearing tiny high-heeled boots that are the same as the black ones Leonora wears. The arms of the chair are human and end in the same long, tapered fingers and polished nails as hers.

The chair, then, shares her most feminine aspects: the red even matches the lipstick that she wears. But this furniture is plainly uncomfortable. It is too small for her and something she has outgrown or has never really been suited to. I can see this from the way she sits: stiff, awkward, and braced against the floor with her out-turned legs and uncomfortable shoes. She isn’t at home in this feminine, childlike seat. Instead, she is dressed for riding and wears jodhpurs and a practical shirt and jacket.

The shirt, which is brown and creased, flattens out her chest to minimize her breasts and matches nothing on the chair. But it does correspond to the brown stripes of the hyena beside her. Carefully, I step around to the left. I study the hyena, which does not scare me. On the contrary: I love its pert, intelligent, neat, female face. This animal, I know from Carrington’s story ‘The Debutante’, was meaningful for her.

In ‘The Debutante’, she befriends a hyena at a zoo. She then arranges for it to take her place at tedious social events connected to the upper-class ritual of ‘coming out’ into society that young girls of her background were expected to do, including being presented at court. In her story, the hyena disastrously fails to impersonate her successfully because of its unpleasant stench and savage manners (it eats people).

The bond between the woman and hyena in this room is strong, but I cannot be sure what Leonora wants me to take from it. ‘The Debutante’ is a satire on the false refinement women are expected to perform in certain social contexts and the hilarious failure of the hyena is a wonderfully liberating tale. In the dreamlike space of this painting, where Leonora seems to have conjured the hyena out of a yellowish cloud of ectoplasm, the relationship between them is less clear.

It is only now that I realise the hyena has blue, human eyes while the figure of Leonora in the chair has acquired the hyena’s yellow, animal eyes in return. The hyena, with its obviously full teats, makes me think of female bodily processes such as menstruation, birth and lactation, and all the pungent physical smells of the body, just like in her story. I turn to Leonora and question her: how is this animal related to you? But she won’t answer, she just continues to gesture towards it as if to acknowledge that she has created the animal and then separated herself from it.

Later in life, Leonora would find motherhood a positive, creative state and would paint with a baby in her arms. I sense that she was surprised by how much motherhood fulfilled and delighted her and I love reading the chapters in Joanna Moorhead’s wonderful biography of her in which Leonora, now living in Mexico City, welcomes her two sons into the messy, fertile space of her studio. But this picture, done in Paris years before when she lived with the surrealist artist Max Ernst, represents an emptier space: an inner stage.

It's time to look at the rest of the room. Excusing myself with apologies to Leonora and her familiar, I go to examine the horse on the wall. I know that Max and Leonora had a rocking horse in the Paris apartment just like this one with a missing lower jaw. Leonora identified with horses from her early years of riding on the family estate and she took the horse as her totem animal in many paintings. But you don’t need to know any of Leonora’s horse lore to notice that the white rocking horse is reflected and repeated by the wild running horse, also white, pictured in a frame or window on the back wall of the room.

Looking back at Leonora, I see that she shares visual symbols with both these horses but especially with the wild, free horse. Her hair stands out in the shape of a mane or perhaps a tail. Only the liberated horse has a mane and tail; the mutilated, nailed-down wooden horse has neither.

I walk to the back of the room. The yellow curtains, dusty and old, part to reveal the scene of the horse galloping through a conifer wood. This could be a window but there is no sill, no glass and no window bars. Forgetting for a moment that I, like Leonora, the hyena and the rocking horse are all already inside a picture, it occurs to me that the wild horse might be a painting. So that would make it a painting within a painting.

Leonora, then, sitting in the chair, is the magician who has taken all these elements: the feminine furniture, the smelly female hyena and the broken wooden horse, and created a new work of art, namely the depiction of the free-running horse on the back wall. She has rejected the overly decorative feminine codes of behaviour of her birth and the childlike role women were assigned by the surrealists. Instead, she has conjured up a new creature with the desire for freedom and wild, bodily life.

As I turn back towards the centre of the room and prepare to step out of this painting and down into the gallery, I notice the shadows on the floor. Each item or creature in the room has a shadow, including the patch of psychic energy which chills me as I walk through it. The shadows know more, perhaps, than Leonora did at the time because war was soon to come. When it did, she and Max were in the South of France and Max, a German, was taken away and interned. Leonora’s mental balance began to falter and after escaping with friends to Spain she ended up confined to an asylum where she was tortured by a psychiatrist who induced epileptic fits. Meanwhile, Max escaped and managed to return to their home to collect his own and Leonora’s pictures (she had not been able to take them with her). If he had not rescued this picture, we might never have seen it or had this chance to explore its surreal, rebellious world.

As I step out of the painting and find myself standing once more on the floor of the gallery, I am aware of others quietly examining the pictures on the walls. I break off the gaze I have shared with the beautiful, imperious Leonora and make room for the next viewer.

I love this way of exploring and analysing an art work. I'm a huge fan of Leonora too. I read somewhere that one of the creatures was supposed to symbolise Max but I can't recall which one.