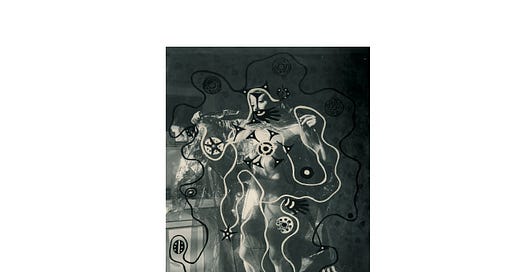

This intriguing image from 1936 was created by the British surrealist Eileen Agar. Her partner took a black-and-white photograph of her holding up a sheet of transparent plastic. Afterwards, she added gouache and ink to the photograph. I have interpreted this image as an alienation from the body but Harriet Baker in Apollo magazine has the opposite view and thinks that the picture represents ‘Agar’s total appropriation of her own image’. What do you think?

By the way, I have recorded an audio transcript of one of my previous imaginary encounters: the one with And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur by Leonora Carrington. It occurred to me that it would be better for my readers to be looking at the image and listening to the words at the same time, rather than scrolling up and down to see the image as they read. The sound quality isn’t perfect by any means and I will work on making it better but do check it out if you have time, and let me know if you liked having the audio as well as the written words.

Meanwhile, I hope you enjoy my take on Eileen Agar’s wonderfully ambiguous Ladybird! A crucial scene in my forthcoming novel borrows this visualisation of a false identity as a veil which can be removed to reveal a more genuine self. There’ll be more news about my novel in the coming weeks.

What is my body? I experience my body through a veil, though it is I who holds up the veil. I have been given this veil, this interpretation of my physical incarnation. I do not know what is written on my soul, only what is written and drawn to describe my body.

The symbols make no sense. They reach back to cave drawings and veer into the occult. They tell me I am the egg and the dark, but I feel only the human impulses of movement, connection, and the desire for shelter and safety.

I have tried to fit myself into these stories and painted my finger- and toe-nails as I have been shown, but I am not very convincing and I miss the mark, inevitably, in these games of pretence.

You have asked me not to look directly at you and so I look away, demurely, while you inspect this body of mine, or is it yours?

If I dropped this veil and looked down at my own naked form, what would I see? My childhood would be there, the marks of motherhood and the loosening flesh of my eventual old age. The bones that have carried me to the places of my life have a different story, a code not expressed in the cryptic swirls decorating this awkward, artificial curtain.

The pattern you have given me makes no sense and yet I cannot experience my body beyond it or without it. Not my arms as they weaken with age, not my belly as it fills with air or food, not even my pelvis as it contracts with blood or desire.

None of these, not even my brave, innocent feet, are known to me behind this gauze of history, society, custom and prejudice.